JT Torres, Jiu-Jitsu & The American Dream, Part 3: From East Coast To West

JT Torres, Jiu-Jitsu & The American Dream, Part 3: From East Coast To West

From humble beginnings in the Bronx JT Torres became one of the most recognizable black belts in America. In Part one we profiled Torres's early experiences of growing up and encountering jiu-jitsu. Part two saw him fall in love with the sport -- read on

From humble beginnings in the Bronx, JT Torres became one of the most recognizable black belts in America. In Part I, we profiled Torres's early experiences of growing up and encountering jiu-jitsu. Part II saw him fall in love with the sport -- read on to discover how he turned his passion into a career.

PART III

When JT Torres received his brown belt, he decided then and there that he wanted to become a black belt world champion. There was no question about it.

He had already begun making an impression at tournaments all along the East Coast. As a purple belt, he fought an incredibly close no-gi grappling match against a Brazilian by the name of Wilson Reis, an established black belt (and later, MMA fighter) fighting under the Team Lloyd Irvin flag. Wilson was teaching at the academy of his friend and teammate Jared Weiner, Irvin's first American black belt.

Impressed by the 16-year-old Torres, Irvin approached JT after the match to invite him to train at his academy in Maryland.

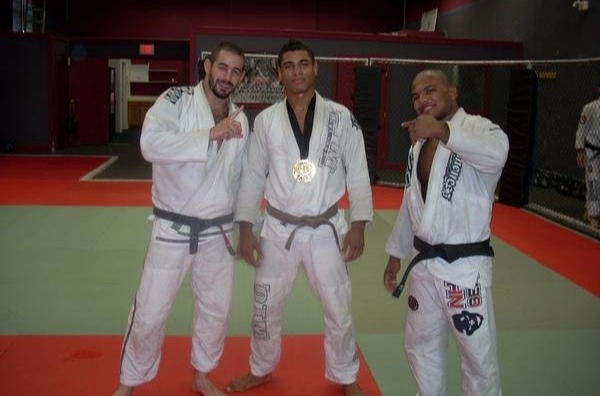

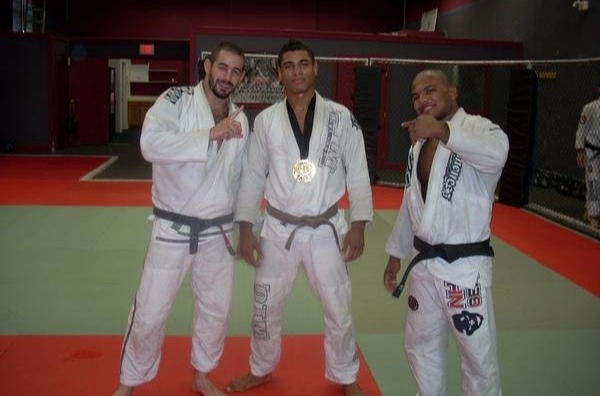

JT Torres with Jared Weiner (left) and Wilson Reis (right). Photo: personal archive

JT Torres with Jared Weiner (left) and Wilson Reis (right). Photo: personal archive

Always cordial, Torres thanked him but didn't follow up on the offer. However, he did compete against Reis several more times, giving the Brazilian a tougher and tougher match. When he received his brown belt, he gave Reis a call.

"You know, I have no ego, I really don't," Torres said. "So I called up Wilson, and I said, 'Hey Wilson, can I come train with you, man? Do you mind if I come roll with you down in Philadelphia?' And he was ecstatic. 'Yeah, man, absolutely! Come down!'"

Following the call, Weiner called Torres directly and extended the offer.

Torres knew that embracing the competition-oriented style of Weiner's BJJ United was the next step toward his goal of becoming a black belt world champion. Like he had done with his first instructor, Peter Clemente, Torres went to his current trainer, Louis Vintaloro, and was honest and upfront about his plans.

"I remember I met with him face-to-face, and I said 'Hey Louis, I think I want to start training full-time with Jared and Wilson. I really want to take my game to the next level.' Louis was a young guy, and he saw that I wanted to compete, and he understood. We shook hands and he wished me luck on my journey."

But JT didn't move to Philadelphia. It was a two-hour drive from his home in Fair Lawn, NJ, to the academy in Philadelphia, but Torres was committed. For nearly two years, he made the drive three times per week, two hours each way. On the off days, he would gather some friends and train wherever he could.

His dedication and hard work started paying off. In 2009, he won silver at the IBJJF World Championships, and then Weiner promoted him to black belt. He was 19 years old.

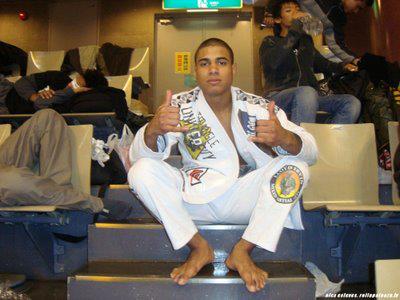

L-R: Bill Cooper, JT Torres, and Roberto Cyborg in 2009.

Imagine a college dorm, minus the drinking and the drugs -- that was life for the TLI fighters living in "The Jungle," a two-level house in the middle of St. George's County, Maryland. The basement was converted into a huge mat space with bunk beds along the wall. By the time the team was established, between eight to 10 guys were residing there, living and breathing jiu-jitsu. They were Irvin's "Medal Chasers."

For the first time in his career, Torres began training two to three times a day, including jiu-jitsu classes, drilling sessions, and strength and conditioning workouts. His performance at tournaments reflected his efforts: He medaled at the World Championships, the Pan Americans, the Brazilian Nationals, and the World and Pan American NoGi Championships.

For the first time in his career, Torres began training two to three times a day, including jiu-jitsu classes, drilling sessions, and strength and conditioning workouts. His performance at tournaments reflected his efforts: He medaled at the World Championships, the Pan Americans, the Brazilian Nationals, and the World and Pan American NoGi Championships.

Then in January 2013, things turned sour.

Two TLI athletes were accused of raping a female teammate. Then the details of a case from 1989 resurfaced in which Irvin himself was implicated and tried in the gang rape of a 17-year-old college student (he was acquitted).

All of his teammates and friends were scattering to the wind -- making the same decision to remove themselves from the scandal surrounding TLI. Torres thought about opening his own academy, but his father advised against it, telling him that he should wait and gain more experience. He thought about training at Marcelo Garcia's academy, which he had visited often in the past.

Then Keenan Cornelius, his main training partner and roommate at the TLI academy in Maryland, called him up. Cornelius was going to California and asked JT's advice on where he should train.

"I was like, 'Man, I think you should go train at Atos in San Diego. Train with Andre Galvao,'" Torres said. "That was a guy who I thought was one of the best jiu-jitsu players -- who I still think is one of the best jiu-jitsu players -- in the world."

Cornelius said he'd check it out. And he asked Torres if he too would come out to California.

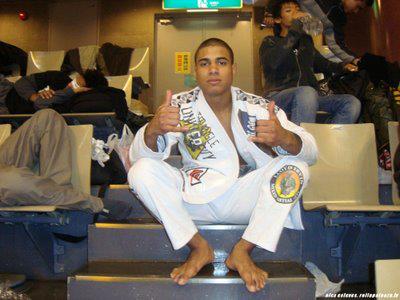

Photo by Luis Lopez

JT hesitated. It would be expensive to move out to California, not to mention the living costs. He had no money. His whole family was on the East Coast, and he had never lived more than a few hours away from them.

Cornelius' words had planted a seed and over the next two weeks -- as he kept Torres up to date about the intense training at Atos, about rolling with Andre Galvao, about how the mats were filled with black belts -- JT's mind was swayed.

Part IV coming Thursday...

PART III

When JT Torres received his brown belt, he decided then and there that he wanted to become a black belt world champion. There was no question about it.

He had already begun making an impression at tournaments all along the East Coast. As a purple belt, he fought an incredibly close no-gi grappling match against a Brazilian by the name of Wilson Reis, an established black belt (and later, MMA fighter) fighting under the Team Lloyd Irvin flag. Wilson was teaching at the academy of his friend and teammate Jared Weiner, Irvin's first American black belt.

Impressed by the 16-year-old Torres, Irvin approached JT after the match to invite him to train at his academy in Maryland.

JT Torres with Jared Weiner (left) and Wilson Reis (right). Photo: personal archive

JT Torres with Jared Weiner (left) and Wilson Reis (right). Photo: personal archive Always cordial, Torres thanked him but didn't follow up on the offer. However, he did compete against Reis several more times, giving the Brazilian a tougher and tougher match. When he received his brown belt, he gave Reis a call.

"You know, I have no ego, I really don't," Torres said. "So I called up Wilson, and I said, 'Hey Wilson, can I come train with you, man? Do you mind if I come roll with you down in Philadelphia?' And he was ecstatic. 'Yeah, man, absolutely! Come down!'"

Following the call, Weiner called Torres directly and extended the offer.

Torres knew that embracing the competition-oriented style of Weiner's BJJ United was the next step toward his goal of becoming a black belt world champion. Like he had done with his first instructor, Peter Clemente, Torres went to his current trainer, Louis Vintaloro, and was honest and upfront about his plans.

"I remember I met with him face-to-face, and I said 'Hey Louis, I think I want to start training full-time with Jared and Wilson. I really want to take my game to the next level.' Louis was a young guy, and he saw that I wanted to compete, and he understood. We shook hands and he wished me luck on my journey."

But JT didn't move to Philadelphia. It was a two-hour drive from his home in Fair Lawn, NJ, to the academy in Philadelphia, but Torres was committed. For nearly two years, he made the drive three times per week, two hours each way. On the off days, he would gather some friends and train wherever he could.

His dedication and hard work started paying off. In 2009, he won silver at the IBJJF World Championships, and then Weiner promoted him to black belt. He was 19 years old.

People always say, 'Oh, you received your black belt from Lloyd Irvin'. He was there, absolutely, but when I got my black belt, it was really from Jared.Shortly after, he accepted an offer he couldn't refuse: move to Maryland and become a full-time TLI athlete. That meant living in the fighter's house rent-free, training full-time, and having all of his travel expenses paid.

Imagine a college dorm, minus the drinking and the drugs -- that was life for the TLI fighters living in "The Jungle," a two-level house in the middle of St. George's County, Maryland. The basement was converted into a huge mat space with bunk beds along the wall. By the time the team was established, between eight to 10 guys were residing there, living and breathing jiu-jitsu. They were Irvin's "Medal Chasers."

We were all super competitive athletes, but you know, it was a house with a bunch of guys in it, all with the same goal. So it was a lot of fun. And it was a positive environment. I remember when one of us was down, or didn't have a good day and didn't want to go train, we would push each other. We would motivate each other. I still look back and reminisce about the good times I had with my friends.

For the first time in his career, Torres began training two to three times a day, including jiu-jitsu classes, drilling sessions, and strength and conditioning workouts. His performance at tournaments reflected his efforts: He medaled at the World Championships, the Pan Americans, the Brazilian Nationals, and the World and Pan American NoGi Championships.

For the first time in his career, Torres began training two to three times a day, including jiu-jitsu classes, drilling sessions, and strength and conditioning workouts. His performance at tournaments reflected his efforts: He medaled at the World Championships, the Pan Americans, the Brazilian Nationals, and the World and Pan American NoGi Championships. Then in January 2013, things turned sour.

Two TLI athletes were accused of raping a female teammate. Then the details of a case from 1989 resurfaced in which Irvin himself was implicated and tried in the gang rape of a 17-year-old college student (he was acquitted).

When I decided to leave, it was a time that there was a lot of negative energy surrounding the team. I remember thinking to myself, 'I've come this far, and my dream is to go as far as possible in jiu-jitsu. I want to become a world champion.'JT first went back home to New Jersey, and he broke down at the front door of his father, William Torres. JT felt lost. He didn't know what his next step would be. He was so close to achieving his dream of becoming a world champion black belt, but he had now lost his team and the stability that came with being a full-time athlete.

And I felt that in the situation I was in, I couldn't really focus on that. There was a dark cloud over our lives at that time. When I decided to leave -- there were a few of us who decided to leave -- I just had to pull the trigger on my next move.

All of his teammates and friends were scattering to the wind -- making the same decision to remove themselves from the scandal surrounding TLI. Torres thought about opening his own academy, but his father advised against it, telling him that he should wait and gain more experience. He thought about training at Marcelo Garcia's academy, which he had visited often in the past.

Then Keenan Cornelius, his main training partner and roommate at the TLI academy in Maryland, called him up. Cornelius was going to California and asked JT's advice on where he should train.

"I was like, 'Man, I think you should go train at Atos in San Diego. Train with Andre Galvao,'" Torres said. "That was a guy who I thought was one of the best jiu-jitsu players -- who I still think is one of the best jiu-jitsu players -- in the world."

Cornelius said he'd check it out. And he asked Torres if he too would come out to California.

JT hesitated. It would be expensive to move out to California, not to mention the living costs. He had no money. His whole family was on the East Coast, and he had never lived more than a few hours away from them.

Cornelius' words had planted a seed and over the next two weeks -- as he kept Torres up to date about the intense training at Atos, about rolling with Andre Galvao, about how the mats were filled with black belts -- JT's mind was swayed.

I thought about it and thought about it, and I said, 'You know what, I'm going to take the leap.' I packed my suitcase. My dad gave me the nod and said, 'Go for it, man.' I got a one-way ticket. I had a couple hundred bucks to my name, and I left for California.At the time, Torres had been dating Iolanda Scotto, whom he had met through a mutual friend. Although they had been together only eight months, he asked her to come with him. She did.

Part IV coming Thursday...