As Competition Career Winds Down, Márcio André Is Building A Larger Legacy

As Competition Career Winds Down, Márcio André Is Building A Larger Legacy

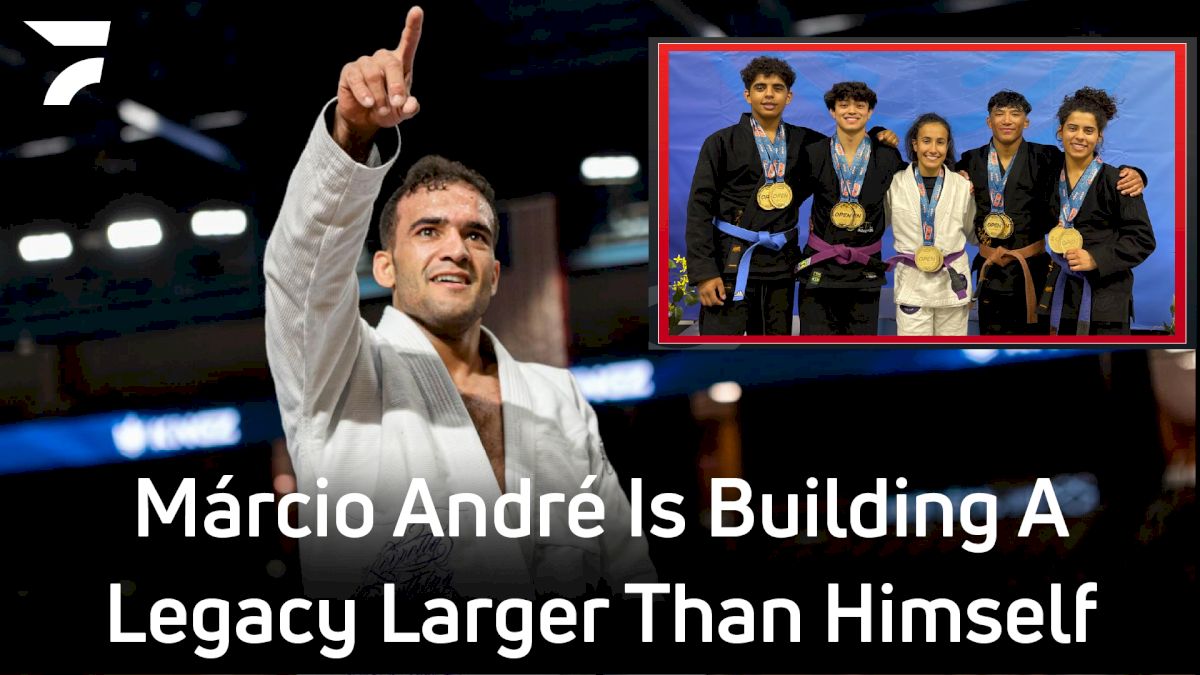

André remains a competitive threat. But his vision of legacy lies less in his personal success & more in the home-grown winning team he's built in Arizona.

In a modern jiu-jitsu scene replete with teenage phenoms and breakout stars, it can be easy to forget about stalwarts on the scene: the consistent, tenured contenders who are always ready to battle and to entertain.

Márcio André is one of such athletes. A three-time European Champion who received his black belt in 2014, André is a generation-crosser when it comes to his jiu-jitsu career, having competed against those who represent the best of their eras in the sport.

“Everyone thinks I’m older than I am!” he laughs, and it is easy to understand why. Though André is only twenty-eight years old, he has amassed both the volume and caliber of experiences that make him seem older than his years, experiences that establish him among the best featherweights of all time.

“I fought legends in the past,” he recounts. “I fought Cobrinha, I fought Rafa Mendes, and guys I used to look up to like Bruno Frazatto. Now I’m able to fight like I don’t know how many generations after that and that’s crazy.”

While Andre’s first few years at black belt put him up against the likes of Hall of Famers such as Rafael Mendes and Cobrinha, his last few years have put him up against the likes of Ronaldo Junior, Jonatha Alves, and longtime rival through the colored belts, Isaac Doederlein. In the last few months alone, Andre has taken on Elijah Dorsey (at Europeans), Andy Murasaki (at the Spyder CHAANCE Invitational), and perhaps most notably, Fabricio Andrey, whom he defeated in the finals to win the 2023 Pan American Championship. It was André’s first Pan title in his nine-year black belt career.

Much like Doederlein, who won Worlds in 2022 after six years at black belt and just collected his second Brazilian National title, André is a case in point in persistence when it comes to achieving excellence at the black belt level. His recent win at Pans has shown the world of competitive jiu-jitsu that André still has gas in the tank to take on anyone. In addition to being a frequent competitor in the absolute divisions, André has competed in weight classes ranging between featherweight, lightweight, and middleweight throughout the course of his career, especially in the last three seasons.

André's victorious run at Pans was as much a triumph of technical excellence and tested experience as of physical and mental fortitude.

In many ways, by the time André stepped on the mat for the first match of the featherweight division, he had already won. He had coached more than half of his competitors onto the podium throughout the course of the tournament, completed an aggressive 20kg weight cut back to featherweight, overcome the last few years of affliction with depression, nagging injuries, and self-doubt associated with his own preparation.

“I wasn’t able to show [my best] in competition anymore because I wasn’t feeling confident," André said. "My mentality of ‘work hard, work hard’ was holding me back because, in my head, I wasn’t working as much as I used to.”

The way André used to work often included four and five training sessions a day, a hard-to-sustain routine, but one that gave him the confidence to perform in some of the most notable runs of his career, including the 2016 World Championships where he faced a firing line of featherweights in Bruno Frazatto, Cobrinha, and Rafa Mendes.

In 2023, he found that confidence again through the volume and quality of his training — and by getting out of his own head.

“For my head to work, I have to train a lot. For me, the fear of not being ready is worse. It wasn’t even the feeling of ‘I want to win.’ It was the fear of not being prepared. This is what pushes me: the feeling of not being prepared, 100% ready.”

His return to 100% readiness at Pans was a work of prioritization and sacrifice. His pre-Pans training schedule was simple but brutal: wake up at four; train until noon. Training largely entailed doing his own cardio and participating in a three-hour competition class, five days per week, alongside his team of competitors. “It’s the only time I have,” he says. The rest of his schedule is packed with private lessons, teaching classes, and managing the business of his academy in Phoenix.

Though André is still young, he speaks about his almost decade-long black belt career almost as if in hindsight, “It was a nice story. I’m blessed to be able to pass through those moments and be here and still compete. So that’s amazing. I’m happy and proud of that.”

Even prior to pulling out of Worlds due to injury, André spoke about the tournament like a “last dance”’of sorts for him.The arc of André’s career increasingly bends in a different direction: less toward continuing to build on his competitive achievements and more toward building the next generation of champions.

“I want to win Worlds, to be honest, and then I want to stop because it’s really hard," he said in an interview while he was still registered for the tournament. "I want to give more attention to my students. I want to be able to give more. I think I give everything I have but it’s not enough for the level we see now."

Coming to terms with the physical consequences of his desire to outwork everyone — including himself — Márcio admits, “I think my time hasn’t passed because I’m too young, but my body doesn’t want to handle it anymore.”

As one chapter ends, another begins: André seems excited to more formally turn the page of his identity from athlete to coach in the coming years. “I compete with [my students] but I’m not a professional athlete. I’m just a competitor,” he says.

André's work ethic, commitment, and leadership by example as “just a competitor” in fellowship with his students is part of what has led his team to recent success. His small-but-mighty team of six is ready to take on the best in the game.

Watch the 2023 IBJJF Worlds live on FloGrappling here!

The greatest teams in competitive jiu-jitsu have a few things in common.

- Invested coaching.

- Technical teaching.

- Dedicated, hardworking students.

- A culture of continuous improvement.

Teams like Alliance, Dream Art, Art of Jiu-Jitsu, and Atos have typically commanded the conversation when it comes to finding and nurturing top-notch talent and transforming it into competitive dominance. But in Phoenix, Arizona, there’s a small but significant band of competitors looking to change that conversation.

Entering the chat: Team Márcio André.

André's stellar return to featherweight may have stolen the spotlight at Pans, but his individual performance is both a consequence of his work with his team and harbinger of things to come from its competitors.

The close-knit squad has a six-athlete roster across the rank spectrum: Caleb and Eliza Nascimento at blue belt, Yasmyn Castro and Kaelin Matthew at purple belt, and brown belts Damian Hosokawa and Mourece Ramirez.

Some of these names may already be familiar to fans keeping an eye on the colored belt scene over the last two years. The rest are looking to make a splash at Worlds and beyond, and under the technical and mental tutelage of André, the team is set to become unstoppable.

André's Blue Belt Roster: Caleb and Eliza Nascimento

Caleb Nascimento: Juvenile 2, Ultra Heavyweight

Caleb Nascimento is affectionately – and intimidatingly – called “Baby Monster” by his teammates. A Juvenile 2 blue belt ultra-heavyweight, Caleb is both the youngest and the largest member of a competition team where all other team members make weight between roughly 110 and 155 lbs. At 16 years old, he is still growing into his body and his game.

The “Baby Monster” pulls no punches when talking about his future career aspirations, speaking plainly about his ambitions of taking on the biggest names in the heavier weight divisions: specifically, Nicholas Meregali and Kaynan Duarte. Nascimento said that when he pivots to training no-gi for the second half of the year, he hopes to avenge his semifinals loss at No-Gi Worlds 2022 against Benjamin Garry Swainston and to face pedigreed peer and 2022 juvenile blue belt no-gi world champion, Achilles Rocha, son of Vagner Rocha.

Caleb said that the most impactful advice he's gotten from Márcio over the years was to trust in his training partners.

“When I start putting that [mentality] into tournaments — that my training partners are better than the people that I fight [in my division] — I’ll start doing a lot better.”

While Caleb could do “a lot better” by his own estimation, he’s already doing quite well on paper. Last year, he won Worlds at Juvenile 1, and in the first half of 2023, he secured double gold at Euros and a silver in the open class at Pans — all while maintaining a high school course load and doing competition training during winter and sprint breaks.

Márcio was Caleb’s age when he won his first World title at blue belt in 2011. “[Márcio] has fought a lot," Nascimento says. "Everything we’re going through, he’s already been through.” Márcio's career is a proof point for Nascimento and the rest of the team that they're being guided by smeone who has experienced the competition nerves, the sacrificies of training, and the coming of age journey growing up in jiu-jitsu.

As a blue belt, Caleb has both the time and the talent on his side to follow in his coach’s footsteps and repeat what André himself achieved: world titles at every colored belt.

The same is true for his sister, Eliza.

Eliza Nascimento: lightweight

Caleb’s sister, Eliza Nascimento, is known as “the quiet one” on the team, but her performances speak louder than words: she’s currently one World Title away from a 2023 Grand Slam at blue belt.

Eliza has had one of the most remarkable seasons of any colored belt athlete this year, with double-gold finishes at both European and Pans in 2023, winning all nine of her Pans matches by submission. Earlier this month, Nascimento continued her lightweight win streak and remained on track for a Grand Slam, claiming a gold medal in her division and a bronze medal in the open class at Brasileiros. For the first two majors of the year, she appeared bound to Double Grand Slam, winning double gold at both Euros and Pans.

Across Euros, Pans, and Brasileiros, Eliza’s match record stands at 25-1 with a submission rate of nearly 70%. Assuming a trend of continued dominance in the coming weeks, Nascimento could become a World Champion and complete her first Grand Slam.

Though Eliza’s performances might make it seem like she was naturally gifted or like she was angling for a championship reputation all along, the truth is Eliza came into her own as an athlete slowly and deliberately over time.

“She was not the kind of student who came to me saying ‘I want to be a champion, because a lot of people come to me and say that," André says. "Her brother, Caleb, was the one who said ‘I want to be a champion’ and I saw [Eliza] more in the corner…Then I’d see her start training. She’s not missing class. She comes more than one time a day. And I was like ‘Hey, are you interested in competing?’ She said, ‘Yes.’’

“At the time, she was behind,” André said recalling the early days of working with Eliza and her losses in 2022 that preceded her breakout 2023 season. “But if you put in effort, you put in commitment, if you believe in your coach and do what he says and he’s good at teaching and is knowledgeable, it’s almost impossible for things to not work. [Eliza] is a good example of that. [Her] work ethic is really good. That’s why she’s had these crazy performances.”

Though others describe her as shy, Eliza is anything but when it comes to her ambition. She’s got her sights on a few things in the near to mid-future: Win her first Grand Slam. Earn her marketing degree. Take on one of the most pedigreed and promising young talents in women’s jiu-jitsu.

“I’d like to face Sarah Galvao,” she says with an earnest smile. As the 2023 gi season nears its end, Eliza already has her sights set on 2024: “Next year, we’ll both be purple belts and in the same weight class. I think it will be a great match.”

Like Nascimento, Galvao is also on track for a Grand Slam this year (at Juvenile 2, having already achieved a double grand slam at Juvenile 1 in 2022).

As much as we’ve already seen from Eliza Nascimento, there’s reason to believe there’s more where that came from. André notes, “She’s not even close to what she can be. And that’s what people don’t know yet.”

If they don’t know, they will soon enough.

André's Purple Belt Roster: Yasmyn Castro and Kaelin Matthews

Yasmyn Castro, roosterweight

“The girls are like our sisters,” more than one of the boys on the competition team will tell you. And Yasmyn Castro does have a fair bit in common with Nascimento. She’s also studying for a marketing degree, has a slightly shy way about her, and when it comes to competition, she’s a tenacious competitor in her own right. Castro won Euros as a blue belt in 2020, and has been a consistent presence on the podium at IBJJF majors as a purple belt: she took silver at Worlds in 2021 and at Euros in 2022, falling short to a worthy competitor in Art of Jiu-Jitsu hotshot Shelby Murphey. Since then, Castro collected bronze medals at Pans in 2022 and 2023, and, just a few weeks ago, clinched another bronze at Brasileiros, submitting her way into the semifinals with two clean finishes off of a triangle setup.

Castro wasn’t always a serious competitor. When she first started training at age fourteen, prompted by her dad’s desire for her to learn self-defense,Yasmyn wasn’t enthused by jiu-jitsu at all. “I was not into it,” she laughs. “My dad used to take my brother to train, and I used to hide in the bathroom so I wouldn’t have to go!”

She started with the kids classes and women’s classes at Gustavo Dantas’ Academy with a role model in Sarah Black, an accomplished Arizona-based competitor who won Worlds at purple and brown belt and took silver at Worlds as a black belt in 2016.

Castro first met André in 2017, when he was teaching two times a week at Dantas’ academy in Phoenix, and followed André when he opened his own gym in 2019.

“I was never really good at jiu-jitsu,” Castro says, thinking back to the days she spent in class waiting for the class to end and getting beaten up by the other kids in class. “It took a lot of effort and I’ve lost so much. I went years without ever winning a match, without winning a tournament. After sticking through that and Márcio giving me more realistic goals, I could see myself ending up on hard podiums training under him.”

Aside from technical improvement over time, Márcio's main contribution to Yasmyn’s game is self-belief.

“He’s definitely encouraged me to believe in myself a lot more. He lets me know that I have good potential in jiu-jitsu, that if I just believe in that, I can go so much further. Having somebody who is so high level and who knows what he’s saying when he says something like that puts a lot of belief in my own heart. It makes me feel confident going into competition, like I can do it, it’s just a matter of getting over my own mind.”

Kaelin Matthews, roosterweight

André had the same effect of cultivating belief on Kaelin Matthews, the newest member of the competition team, who joined just less than two years ago in the summer of 2021. After graduating from high school and wanting to take jiu-jitsu more seriously, Matthews decided to move from Tuscon to Phoenix with the express intention of going full-time into jiu-jitsu and training under André. Four months in, he found the first glimpses of the success he was hoping to achieve in jiu-jitsu, winning bronze at the 2021 World Championships at blue belt roosterweight.

“I competed at Pans and lost in the quarterfinals in the last few seconds. [Worlds 2021] was my second major competition under Márcio, and when I was able to place that day I thought, ‘Man, I can really do this.’ I always knew it was the right team but that was when I really believed it.”

In addition to finding his competitive stride under Márcio, Matthews also found a family for himself on and off the mats. His mother and sister had left Arizona and Matthews moved to Phoenix after his high school graduation without any connections. Now, he has a family in the competition team, in the families of members of the competition team — all the other members’ families are local – and in the broader membership body of the gym.

“It’s not a gym just for competitors,” Márcio notes. Kaelin echoes, “For the killers of the competition team, there’s at least another ten who don’t compete who are monsters. Even the people who are training once a day are really good.”

When speaking of Márcio's skill as a coach, Matthews refers to three key ideas. The first is the absence of ego. “He doesn’t try to force his game or his way onto us,” Kaelin said Márcio directs Kaelin and his fellow competitors to study and learn from other top-notch athletes rather than sticking purely to emulating André's own game and style.

The second is a focus on continuous improvement. “Even when we win, he always gives us something to work on. It’s never just relishing the win. [The message] is never ever ‘you fought perfectly.’ It’s ‘let’s focus on these things.”

The third is a constant sense of presence. “Even when he’s not there, he’s there, in our heads.” Or, as it turns out, available on FaceTime.

One memorable moment for Matthews is a story from Euros 2023: Márcio had not yet arrived at the venue, and Eliza was about to approach the mats to compete. Unable to make it on time to coach that match, Márcio deployed Kaelin and Damian as his lieutenants. The two boys split their earbuds, put Márcio on a video call, and zoomed in as much as they could to let him see the match. “We weren’t black belts so we couldn’t get down [matside in the arena] so we’re just zooming in and screaming [Márcio's coaching cues].” Márcio's commitment to presence – even if virtual – goes a long way with the competition team.

Another part of the respect Márcio commands as a coach comes from not letting the team forget that he, too, is a competitor. During the Pans camp, Márcio's compulsive refusal to be outworked didn’t just apply to his opponents – it applied to his own students, serving in their roles as his training partners and teammates.

“You know how everyone says, ‘Oh, there’s someone out there doing more than you’? He’s that guy.”

Throughout the camp, Kaelin recalls Márcio being at the gym up to two hours before the rest of the team, “sweating, running, doing drills,” or simply showing up earlier for the sake of reinforcing the message that he was there, doing more.

Referring to Márcio's ultimate, winning performance at Pans, Kaelin notes with awe, “I don’t think I could have done four or five days of traveling, making sure you’re there, coaching, studying, cutting weight, doing all that stuff while hungry.”

As a competitor with aspirations of fighting the likes of Mikey Musumeci and Thalison Soares, Matthews sees what it will take to make it at the highest level. He’s seen it in Márcio, he’s seen it in his peers, pushing each other to improve every day.

Everyone is there, paying the tolls in hard work needed to come out on top and win.

The Brown Belt Squad: Damian Hosokawa and Mourece Ramirez

Damian Hosokawa: light-featherweight

Damian Hosokowa is known by his peers as “the loud one” or “the crazy one.”

“I always want to put on a show,” he says, and whether cracking jokes in the training room or animatedly dancing at the beginning of the match, Hosokawa radiates energy and swagger, eager to perform.

“You know when a person has a mental block? He doesn’t have this,” Márcio says of Damian’s abilities. “If the kid is not his level or higher, he will submit, he will smash. He’s like, ‘I know what I do, I know what I’m going to do, and I’m going to go out there and do it.’”

Hosokawa’s eventual arrival on André's team seems like kismet in hindsight. He had competed against Mourece Ramirez multiple times in the local jiu-jitsu scene in Arizona. He believed early on that becoming training partners with Mourece would help the both of them realize their competitive potential.

“Me and Mourece had always been talking about training together since we were juveniles. After [the tournament where we first competed], I knew that he and I needed each other to become the best version of ourselves, and training together would be the best. We finally made it happen and ever since then, it’s been through the roof.”

Hosokawa ultimately landed under André in the aftermath of a local competition where he had lost to one of André's longtime competitors, Domenic Hurtado. Hosokawa left the tournament with admiration and respect for André, and reached out to him to express his interest in training under him.

“That kid is a talent,” André notes. “The problem with him was that he was never consistent. I was never able to work with him 100%.”

Hosokawa will be the first to admit this: he started jiu-jitsu when he was five years old and trained on and off for the next fifteen years, competing through the kids and juvenile ranks, but never maintaining a steady rhythm. In 2022, he took nearly the entire year off, spending some time in California and using the hiatus to evaluate his ambitions in jiu-jitsu.

When he returned to Arizona and came back to André's train at the end of 2022, Hosokawa was determined to go all-in on jiu-jitsu and do the work to achieve his championship ambitions, starting with the 2023 European Championships.

André wasn’t fully sold, however.

“Márcio is brutally honest. If he doesn’t think you’re training enough or are serious enough, he’ll let you know,” as teammate Yasymyn Castro puts it. “He won’t let you slack off on your own goals, but also is not going to chase you down for them. He’ll tell you’re not doing enough, but that is on you to fix.”

Wary of Damian’s inconsistency and holding true to his brutal honesty, André gave Hosokawa an ultimatum in the run-up to the 2023 European Championships: “If you miss even one day [of training], I’m taking your name off [the roster].”

Hosokawa met André's expectations and stayed on the roster for Euros, putting on an impressive performance as he stacked up four wins to reach the finals. Losing narrowly by an advantage and coming home with silver, Hosokawa was emotional after the loss. In light of Damian’s recent hiatus and history of inconsistency, André saw the loss as a test of both Hosokawa’s resolve and his determination to continue the course as a competitive athlete.

“I said to him, ‘Now, what I want to see is how you are going to deal with this. Are you going to go back there, do better, train more, work hard, or are going to accept that you lost? He said, ‘No coach, I’m gonna work.’ And he did.”

Hosokawa proved himself resilient and consistent, coming back stronger from his loss in the finals at Euros to win the Pans purple belt light featherweight title two months later.

“[The loss at Euros] was a hard pill to swallow, but I just trusted in what Márcio said and we went back, trained really hard, and I knew that if I just kept on training and followed the path that we were on that nobody was going to be able to stop me at Pans.”

Watching Márcio's own resilience and comeback at Pans was inspiring for Hoskawa and the rest of the team.

“Márcio always has so much passion for us when we compete. To see him fulfill his dreams as well…you know, we’re a small competition team, so for him to succeed, it’s a happy thing for all of us…It was awesome to see him come back at featherweight and show [the world] who Márcio is. The Márcio we know, everyone else got to see again.”

Newly promoted to brown belt, Hosokawa will be making his debut at his new rank at the World Championships–but the brown belt is just a stepping stone. “All the work is for black belt. [Márcio] always says no one cares about your colored belt accomplishments when you get to black belt.”

Hosokawa says he's now fully committed to the work it will take to face the likes of Meyram Alves and Diogo Reis, two athletes he hopes to match against when he eventually reaches black belt.

“Márcio has this saying – we all say it – that we have to ‘pay the price’ to become a champion. If you let other people work harder than you, how can you expect to be the best?”

Mourece Ramirez: featherweight

Described as “a freak athlete” by his teammates, Mourece Ramirez fondly recalls a childhood jumping on trampolines and watching WWE, his love of movement and martial arts emerging as early as five years old.

Engaging in a variety of sports as he was growing up, his twin passions became jiu-jitsu and wrestling, which he started between ages ten and twelve. As Mourece grew older and became a competitive grappler as a teenager, he started dreaming about becoming both a state champion wrestler and a jiu-jitsu world champion. Both dreams came true in 2021, when Ramirez became an Arizona state champion in wrestling and an IBJJF World Champion at purple belt.

He first came into contact with Márcio as a green belt training at Gustavo Dantas’ academy, and when Márcio opened up his own school, Ramirez crossed over, got his blue belt under him and stayed with Márcio through the ranks and ever since.

“I’ve never had a relationship with a coach like the one I’ve had with Márcio. He knows jiu-jitsu to the core.” Speaking of André's strengths as both a coach and mentor, Ramirez notes the breadth and depth of his knowledge along with his commitment to the team’s continuous improvement:

“Questions you didn’t even think of, he’ll answer for you. He’ll break down tape, he’ll break down our jiu-jitsu, he’ll give us another direction to look at. We’re constantly evolving, never not evolving, and he’s helping us improve every single day. ”

Ramirez has reaped the fruit of that continuous evolution and improvement, becoming the most decorated name in André's squad second to only André himself. At purple belt, Ramirez won both the 2021 World Championship and 2022 Pan Championship. Barely three months into his brown belt, he took silver at 2022 Worlds, facing Thalys Pontes in the finals. At the end of the year, he showcased his skills outside of the gi with a winning debut against Queixinho black belt, Keven Carrasco, at Tezos Who’s Number One in November 2022.

Out of the entire competition team, Ramirez holds both the highest rank and the longest tenure under André. He also holds something that few people can claim in the last few years of competitive jiu-jitsu: a win over Cole Abate, whom he faced in the semifinals during his triumphant run at Pans in 2022.

Looking back on his breakout match against Cole, he doesn’t recall a sense of intimidation – just flow and joy.

“I was so happy to be out there. It wasn’t like I was fighting Cole. It felt like I was sparring with a teammate. I wasn’t really nervous because I’ve fought good guys, too: back at the 2021 Worlds, I had a sick bracket – a Pan Champion, a Brazilian Nationals Champion. [Cole] won ADCC trials and was dominating [that year], but that did not faze me. I’ve fought Kade Ruotolo, I’ve fought really good guys before. All the competition, all the training that led to that point [of fighting against Cole], I was ready.”

Even though Ramirez achieved significant renown for his run at Pans in 2022, he doesn’t believe that run represents the full scope of his jiu-jitsu. “I felt that tournament, that day–that wasn’t even my best performance. Now it kind of bothers me a bit because I’m like, “Man, I could have done way more in that fight,” regarding both his semifinal match against Cole and his finals match against Cole’s teammate, AOJ’s Gustavo Ogawa, who would win Pans in 2023.

André shares the sentiment, that there’s more Ramirez can do and that fans – even if they’ve seen him winning, have not yet seen what Ramirez is capable of. “I know his level. I know what he can do,” André says, “but the world needs to see it.”

Fixing technical mistakes and growing his maturity as a competitor are the two key areas of focus for Ramirez in the final lap of his colored belt career. As the athlete on the team closest to competing at the black belt level, Ramirez is acutely aware that the days of looking up to certain competitors are coming to an end, with the days of competing against them about to begin.

Márcio has been priming Mourece and his teammates for the long game, and Mourece says he's excited for the opportunity to test himself against the best names at black belt when the time comes. “I want to fight as much as possible, to fight people who are going to make me better and to challenge myself to the highest possible level. I want to fight Diogo Reis, Lucas Pinheiro, Diego Pato, all those guys. I know they're going to make me better overall as an athlete.”

More than anything else, Ramirez says he cares about having no regrets with regard to his athletic career. In a similar vein of André's mantra of “paying the price” to become a champion, Ramirez’s personal refrain is “shoulda, coulda, woulda”. Regardless of the arc of his career or its outcomes, he doesn’t want to look back on it and think he should have, could have, or would have done anything differently.

As for what success looks like in living without regrets in his jiu-jitsu? It’s simple but significant. “I want to be able to go to an IBJJF World Championship at black belt and showcase my jiu-jitsu to its maximum potential. That’s my goal. Whether I win or lose, that’s what I want.”

Márcio André: The Coach

It’s been almost ten years since André completed his own colored belt career, winning Worlds at blue, purple (twice), and brown between 2011 and 2014. He has been where his students are, lived their every experience, intimately knowing what it takes to reach the top at these stepping-stone milestones on the road to a black belt career.

But there are two important differences between André's own experience and that of his students: choice and support.

“Being an athlete is always hard because we never know what is going to happen. An early injury or something can happen. When I started, it was the same thing, but I didn’t have another thing I could do. I didn’t see myself doing another thing [other than being an athlete] to be honest.”

André's athletes come from supportive families – or have found one in the competition team. They have other options and avenues available to them aside from professional jiu-jitsu.

“I came from a really different situation from them. They have the resources to go to a good college if they can. But the good thing for me and for them is they have good parents that support and help and have their back.”

André also has their backs, whether it’s in coaching them to the top of the podium or to another form of success in making a career out of jiu-jitsu. “I tell them, 'I will help you open a gym, I will help you with making a business,'” André says, promising to support his team members beyond the time-bound nature of their competitive peak.

Perhaps this is what makes the relationship between André and his athletes so strong.

André made a life out of jiu-jitsu because he believed he could not do anything else. His students choose to make a life out of jiu-jitsu even though they could do anything else. He honors that commitment with his own, serving as both peer and patriarch of the “family” that is the competition team.

For all the places they could be or things they could be doing, André and his athletes choose each other: learning from leaning on each other, sharpening their skills and improving every day, “paying the price.” Coming into Worlds, the unit intends to realize the promise set in the training room for 2023.

“This will be the year for Team Márcio André. This will be our year.”